Contents -

Previous Article -

Next Article

Contents -

Previous Article -

Next Article

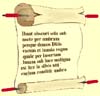

The early books written on papyrus and animal skins were rolled up on a wooden dowel. To read the "book", the reader would take the end of the scroll and start unrolling it, or rolling it onto another wooden dowel if one was available. As he rolled the manuscript from one stick to the other, he could read a small section at a time, depending how far apart he wanted to stretch his arms. A leather label was attached to the end of the scroll or the end of the stick so that the library browser could see what it contained. Libraries were often found in the homes of the wealthy and powerful people in the ancient Greek and Roman world. Often, these libraries contained many rolled books on racks, all with their labeled ends sticking out toward the reader for easy access and identification.

![]() During the early Roman Empire, a revolutionary change in the form of books and other written records was taking place. Though it does not seem at first glance to be such an important innovation, the changeover from books in the form of a rolled manuscript to a book that was bound along one edge was nothing short of earthshaking. For the first time in history, a reader could flip through the pages of a book instead of laboriously rolling a scroll from one hardwood stick onto the other in order to find the particular place in the text he or she was looking for. This saved the reader hours when it came to looking up information. It also made it easier to keep written financial and legal records as well as account books of all kinds. This new format for the printed word was also more portable. The pieces of cowhide used to make parchment could be much smaller now and the finished book was of a size that was a lot easier to carry around. Binding the pages together in this way made it possible to include a table of contents that would directly reference a chapter or an item of interest to a page number. A very similar revolution occurred 1900 years later when computers switched over from magnetic and paper tape readers to disk drives that could access any information anywhere on the disk and fetch pieces of information in any order needed. Both the invention of the bound book and the computer disk drive served to speed up human access to information by a factor of several hundred. This multimedia title you are now using is the latest innovation in the ongoing evolution of books. Indexes, cross referencing, and information searching are built into the document and are handled speedily by the computer with the user only having to click the mouse a few times or type in a few words to search for.

During the early Roman Empire, a revolutionary change in the form of books and other written records was taking place. Though it does not seem at first glance to be such an important innovation, the changeover from books in the form of a rolled manuscript to a book that was bound along one edge was nothing short of earthshaking. For the first time in history, a reader could flip through the pages of a book instead of laboriously rolling a scroll from one hardwood stick onto the other in order to find the particular place in the text he or she was looking for. This saved the reader hours when it came to looking up information. It also made it easier to keep written financial and legal records as well as account books of all kinds. This new format for the printed word was also more portable. The pieces of cowhide used to make parchment could be much smaller now and the finished book was of a size that was a lot easier to carry around. Binding the pages together in this way made it possible to include a table of contents that would directly reference a chapter or an item of interest to a page number. A very similar revolution occurred 1900 years later when computers switched over from magnetic and paper tape readers to disk drives that could access any information anywhere on the disk and fetch pieces of information in any order needed. Both the invention of the bound book and the computer disk drive served to speed up human access to information by a factor of several hundred. This multimedia title you are now using is the latest innovation in the ongoing evolution of books. Indexes, cross referencing, and information searching are built into the document and are handled speedily by the computer with the user only having to click the mouse a few times or type in a few words to search for.

The old scrolls or rolled books were still popular even after the invention of the bound book. The word for scroll was VOLVMEN in Latin (the second 'V' makes a long 'U' sound) and the word for a bound book was CODEX. It is from these words that we get our own words for encyclopedia volume and law codes. By the end of the Third Century, most books were of the CODEX kind with a few very ornate public documents still produced in the form of a VOLVMEN. In the pictures displayed in this section on writing, you can see both kinds being used by Romans, as well as the very handy wax tablet and stylus used for jotting down everyday notes and for schoolchildren's assignments.

Go to next article:

Go back to previous article: