Contents -

Previous Article -

Next Article

Contents -

Previous Article -

Next Article

After the persecutions under Gallienus and Valerian I, the government fervor to root out the Christians died down and life for the Christians of the Roman Empire became relatively peaceful. Many Christians even occupied important government posts as magistrates in imperial service or in town, city, and provincial governments during the reign of Diocletian. In fact, Diocletian’s minister of finance was a professed Christian who later died for his faith. It is also believed that Diocletian’s wife and daughter were Christians as well. In earlier years, lurid stories had circulated about how Christians sacrificed their infants or drank blood in secret rites held in the Catacombs at night, but these rumors no longer circulated by the beginning of the Fourth Century. Christianity had become very much a mainstream religion sharing the stage with other religions of the empire. The person from whom you bought your bread or who repaired your saddle and harness was likely to be a Christian.

All was not well for the Christians, though. The Third Century had been a time of disaster and civil war for the Roman Empire. Diocletian had come and put an end to all the chaos and terrible economic times and had restored order to the government. He was looked on as the savior of the Roman world by many.

Though the Christians were neighbors, they had always set themselves apart from the religious worship of the Romans. The Romans believed that sacrificing to their gods insured security for the empire, victory in battle, and good seasons with plentiful crops for the farmers. They felt it was their civic duty to sacrifice and that if they neglected to honor their gods, their gods would abandon them to the kinds of troubles the empire had seen during much of the Third Century.

Consequently, when Diocletian was told that the Augurs (priests who read signs from the entrails of sacrificed animals) could no longer predict the future or that the Oracle at Delphi no longer gave reliable advice because of the hostile attitude of Christians toward the old gods, he faced a difficult dilemma. It is not known whether Diocletian actually believed in the powers of the traditional gods or not. It was a fairly enlightened age and many educated people doubted that the gods had anything to do with the course of events. No one would publicly denounce the traditional religion, though. The general feeling was, if someone wished to believe, it was up to them and they should not be dissuaded. But for Diocletian to keep the support of the people, he had to do something about the Christians.

In February, A. D. 303, Diocletian issued an edict commanding everyone to sacrifice to the pagan gods. Persecution started first in his own court and the court of Galerius. Then Christians in the army were systematically weeded out. The bishops and leaders of congregations were arrested, and one entire town in which everybody professed to be Christian was burned along with all the men, women, and children in it. Officials in charge of the persecution searched out Christians by checking the tax rolls.

Eusebius states that many Christians were tortured horribly, having tongues and eyes cut out, bodies crushed, and feet chopped off. They were strangled, hanged, and burned with molten lead or red-hot irons. Often, they were flogged over every part of their body before being put to death.

Surprisingly, the persecution was not enforced equally in all parts of the empire, nor was it directed at everyone who was a Christian. It was mainly those in high office or who were leaders in the church who were targeted and relatively few of the common people suffered. The idea was to "decapitate" the church by removing its leaders, and the church itself would die out in a few years. The persecution was carried out more intensely in the East than in the West. Galerius and Maximinus II were probably the most rabid persecutors, especially after Diocletian’s abdication. Maximianus and Constantius Chlorus were only lukewarm in their persecutions, and ignored the imperial order in many cases.

Finally, the people had had enough. Efforts to gain popular support for the persecutions failed to produce results. Galerius died of natural causes (a dreadful disease, according to some reports) in A. D. 311. Maximinus II had a difficult time drumming up any enthusiasm for the persecutions. Even his official requests to the cities for the preservation of the ancient rites brought little response.

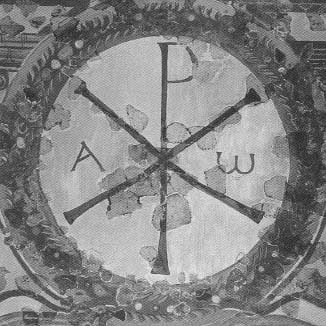

In 312, Constantine defeated Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Constantine had seen a vision in the sky showing him the sign of Christ and assuring him that "In this sign shalt thou conquer". When the prophecy came true, Constantine gave the credit for his victory to Jesus Christ. In A. D. 313, his Edict of Milan promised toleration for all forms of worship and ended forever the Roman persecutions of the Christians.